Tragic floods in Spain – a local overview

Floods in Spain – In the early hours of October 29, 2024, I was woken up by blinking lights. I saw my room turning from night to day and back to night as if the lights were being switched on and off constantly. As I woke up, I thought we had forgotten the TV on, and that it was showing something strobing. But the light was not coming from lamps or from the TV; it was coming from the windows – more precisely, from thunder bolts that illuminated most of the skies. It didn’t make almost any noise, though; I had never seen something like that. I made a video.

AEMET, the national meteorology institute, is constantly monitoring the weather. I do receive receive their alerts (or better saying, my Alexa receives it, and show a triangle where it reads ‘Yellow Alert’) but that’s it – what exactly does it mean and what should I do with that information? Stay home, run for the mountains or just take an umbrella? For the most part of the time I’ve been living in Spain, the only thing I did about it was… to ignore it.

You see, the area has been under a persistent drought for years, since before I arrived here; I’ve seen this alert multiple times and often it didn’t even rain; up to now, the alert did actually raise hopes of a good rain that would ease the droughts. But that was changing right while I watched the non-stop lightning.

Floods in Benalmadena (October 28 and 29)

The lightning pattern lasted for more than an hour. As I watched, and couldn’t sleep anymore anyway, I checked for strobe lightning online. Turns out there is such an aptly named weather phenomenon, and I believe that is what was going on. According to Sur in English, there were more than 20.000 thunder bolts that single night. Next morning, in Benalmadena, the strobe lightning was the talk of the town, and nobody I talked to had ever seen something like that before. The rain brought branches and other pieces of vegetation to the beaches, and the sea color changed from the usual blue/green to muddy brown.

The rains from October 28 and 29 caused some punctual damages. Water entered a few houses and notably, the lower level of the Centro de la Historia de Benalmadena flooded. That was, in general lines, the extent of the problem in Benalmadena. That is not even close to what was happening, at the same time, up on the riverbed of the Guadalhorce, the main river in Malaga province.

Floods in Álora and in the Guadalhorce Valley

On the same day as the strobe lightning, October 29, Álora was flooded. The devastation in Álora was immense: homes received up to 1.5m of floodwater; crops in this agricultural area were completely flooded; one high-speed train was derailed. I was astonished and heartbroken when I read the news – I had been visiting Álora just two months earlier and was (I still am!) impressed by this bucolic and remarkable town. Álora has such a long and rich history; people that helped me when I couldn’t find a safe way back to the train station, people that are nice, work hard, live from and for agriculture and are proud of their work – and may now have lost it all.

While there, back in August, I took this picture from the grounds of the 1000-year-old castle of Álora, overlooking the lower part of the town:

After the rain, this was one of the pictures that illustrated the news of the floods:

And this is a picture of part of the completely dry riverbed in August. It was unimaginable that 2 months later, it would inundate Álora and much of the Guadalhorce Valley:

The area where Álora is, the Guadalhorce Valley (Valle del Guadalhorce), received most of the rain flood in Malaga and in Andalucia. The Valley also includes Pizarra and Cártama, both heavily affected by the floods. This whole region is both an agricultural area and a suburb of the city of Malaga, connected through the C2 train line.

If there is a silver line to this whole tragedy, it is that at least in Andalucia help was fast; more than 40 people were rescued by helicopters or boats. Lives were saved thanks to the fast action of the local emergency agencies, in particular the Guardia Civil and the firemen.

It is hard to compare tragedies. To those affected in Andalusia, this is traumatic event with lifetime consequences, permanent losses of resources and income. Álora, Cártama and Pizarra still need help. Stories like the one of Clotilde de Luque, a single mother who fears losing the guard of her daughter now that she lost her house in Cártama to the flood, need more attention. Families of the Valley need help.

The stories of the losses in the Guadalhorce Valley were being told on the news, and their difficulties were on the spotlight, but just very briefly, because later that same day, a larger catastrophe hit Spain: the DANA reached Valencia.

Floods in Valencia

The first time I heard or paid attention to the word DANA was when it reached Valencia. Up to that point, it was just rain or flood. DANA means Depresión Aislada en Niveles Altos – something like ‘isolated depression on high levels’, which in turn doesn’t mean much for those of us who are not meteorologists. The important part is that this weather phenomenon is known to happen in the Mediterranean and to cause very heavy rain; moreover, the DANA moves erratically, making it hard to forecast where, when and how much it is going to rain up to when it is about to start.

The Guadalhorce Valley was hit by the floods around the morning of October 29; Valencia, in the evening of the same day.

AEMET, the Spanish meteorological service, knew about the rains approaching Valencia. It did qualify it as a red alert event – the maximum level possible. And it published it on Twitter / X. Now, here starts the political side of the tragedy in Valencia, so we have to go by parts. According to RTVE noticias, this is the bulk of what happened:

– the AEMET publishes the tweet around 8 am. A bit before that, it had already sent information to the Generalitat Valenciana (the govern of the Autonomous Community of Valencia, which includes the provinces of Valencia, Alicante and Castellón. The Generalitat is equivalent to the Junta de Andalucía, which governs the Autonomous Community of Andalusia) and to the agency responsible for monitoring rivers in the area, the Confederacion Hidrográfica del Júcar (CHJ).

– The Generalitat could have opted to send alerts to the phones of the population at that moment, but it didn’t do it, perhaps fearing it could create unnecessary panic.

– Around noon, the CHJ sent an alert to the Generalitat, informing of the increasing volume of the river Poyo. The Generalitat decides to inform the municipalities to tell the population to avoid getting close to rivers and ravines.

– Around 5 pm, a meeting is held to decide how to proceed. The situation that motivated this meeting was not exactly the floods, but the fear that a water dam would not resist the water increase. At that moment, several towns were already flooded.

– Finally, the alert is sent to the population at 8:11 pm, still because of the increased risk of water dam failure (the dam, by the way, resisted).

As we now know, when the population in Valencia province received the alert on their phones, it was already much too late. Houses were already flooded in many areas; in others, where it was barely raining, the full comprehension that the nearby river was about to overflow in a blink of an eye was more than the alert conveyed.

The second situation – a flash flood – is what happened in Paiporta, a town close to Valencia, that was on the way of the rain water that fell uphill, in Chiva. It barely rained in Paiporta.

To make things worse, the emergency services either could not reach the affected areas or were not activated immediately. The army – the army! – published a note informing that they were looking forward to help, but had not been mobilized yet by the government. Meanwhile, the many layers of the government were busy blaming each other, trying at all costs avoid being called responsible for the tragedy that was claiming more lives as the hours passed, and has claimed more than 200 as of this writing.

Volunteers’ solidarity was the main source of help right after the flood in Valencia; as the days went by, official sources reached the affected areas.

Floods in Catalonia

AEMET did give the alert that Catalonia was to be the next victim of the DANA days before it happened, while the situation in Valencia was critical and flood risk reports and news were catching everybody’s attention. Too late to prevent major material damage, but early enough to save lives.

The main consequences in Catalonia, as of this writing, were the closing of the airport of Barcelona, El Prat, and the floods in Cadaqués, in which more than 30 vehicles piled up under a bridge – but without deaths.

As of this writing (November 12, 2024), Andalusia and Catalonia are still expecting more torrential rains, and Valencia is still looking for victims.

Understanding the amount of rainfall

It’s hard to fully understand how much water it takes to cause each level of destruction described here. It certainly depends on more than just the amount of water – type of terrain, terrain conditions, inclination, permeability, riverbeds existence and quality, vegetation and so much more can affect the outcomes. Still, a bit of reference is needed. Saying that 1mm of rain is equivalent to 1 liter of water/m2 (is true) but may not clarify much; so, for reference, here are some amounts:

Reference values:

a normal month of October in Málaga: 58 mm of rainfall (source)

a whole (normal) year in Valencia: 454 mm (source)

How much it rained during the events described here:

Benalmadena: about 70 mm of rainfall in 2 days – Oct 28 and 29 (source)

Álora: about 170 mm in 2 days (source)

Chiva (Valencia): about 500 mm in 1 day (source)

Catalonia: between 200 and 400 mm spread in 15 days (source)

Where to get rain alerts

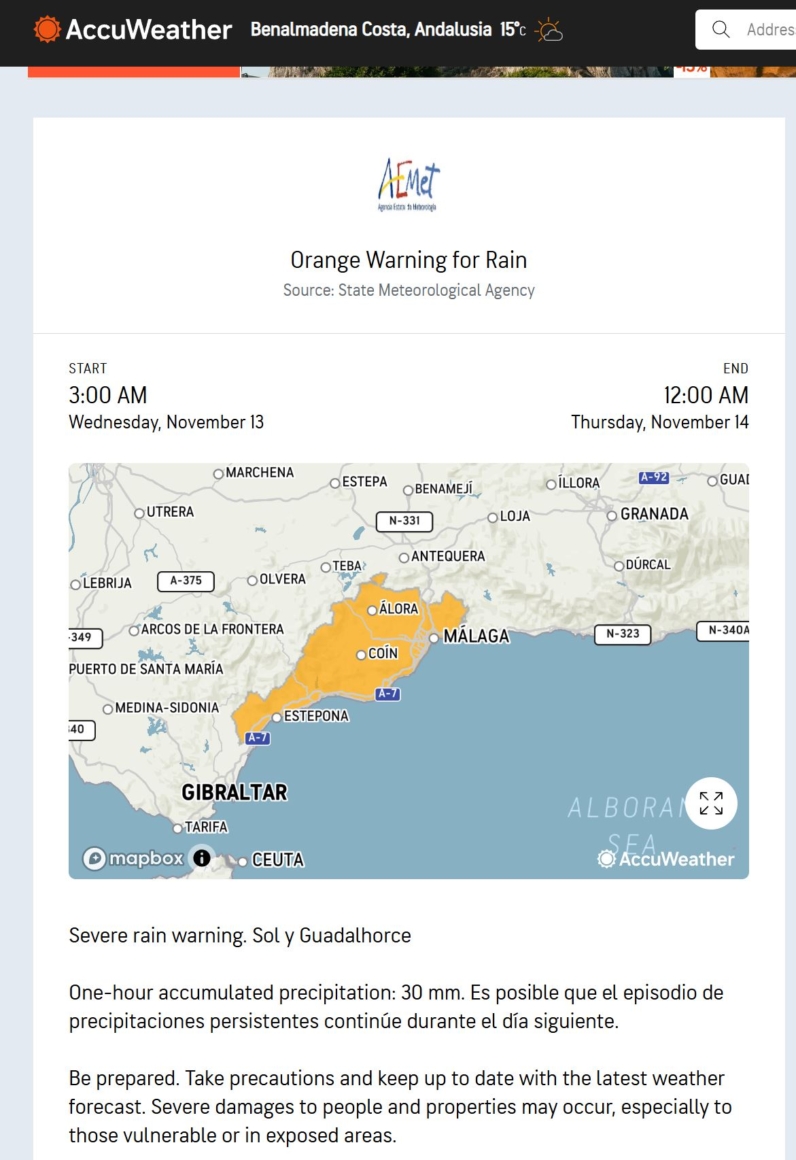

Accuweather

In Spain, Alexa gets information from Accuweather which, in turn, gets it from AEMET. If you want to get the information directly from AEMET, you can follow them on Twitter (aka ‘X’ :P). On the AEMET site, this information is quite hard to come by. On Accuweather, on the other hand, alerts are on the first page – that’s where I’ve been checking. Talking about it, there is a new Orange Warning for Malaga on Wednesday, November 13:

Phone Alerts

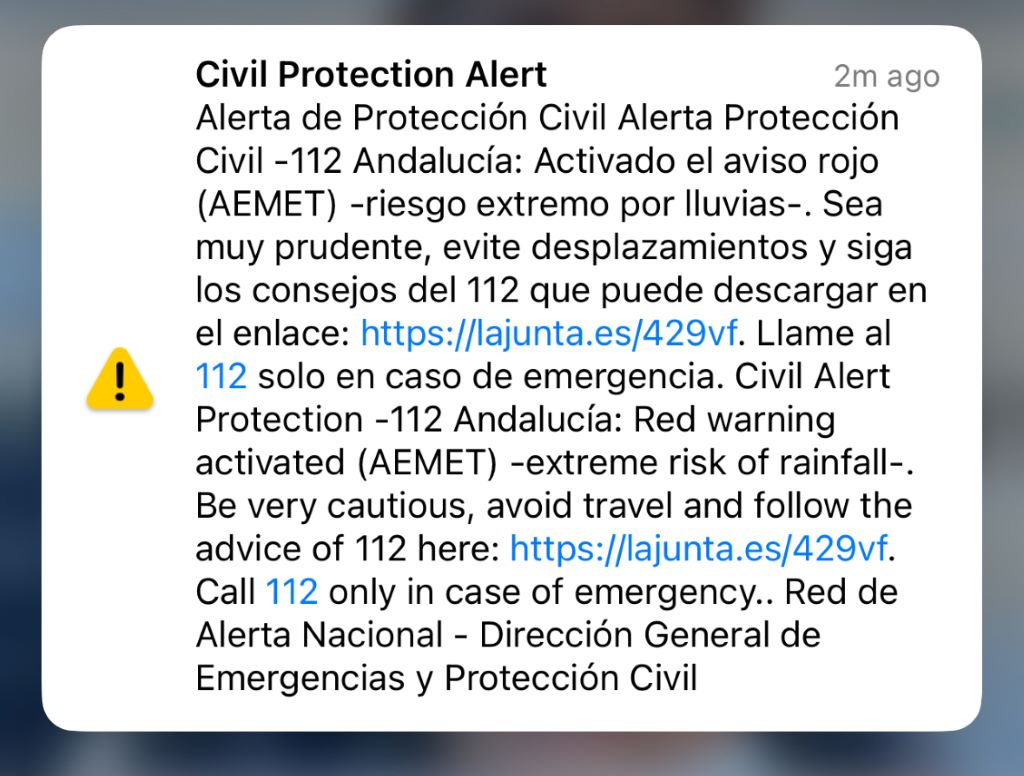

If the Autonomous community decides to send an alert by phone – which, after the Valencian fiasco, is likely to become more frequent – you need to be able to receive it. Surprisingly, it is not set by default; you have to enable it.

If you have an iPhone, check your settings / notifications, then scroll all the way to the bottom and you should find a place where it reads ‘Es-Alert’. Activate the ‘Civil Protection Pre-Alerts’ there. For Android phones, go to settings / safety and emergencies / allow alerts. If you read Spanish, here is a step-by-step with pictures for both types of phones.

That being said… I’m in Malaga, there’s an orange alert for tomorrow, my phone alert is active, and I’ve received nothing – nada, nada – there from the Junta de Andalucía. The towns in Malaga Province (as far as I know) can’t send the alerts to phones, but they are posting alerts on their respective Facebook pages.

Edit: later on November 12, AEMET increased the risk level to red and the phone alert was activated for the first time ever in Andalusia. We received the alert at around 11 pm in Benalmadena – loud and clear!

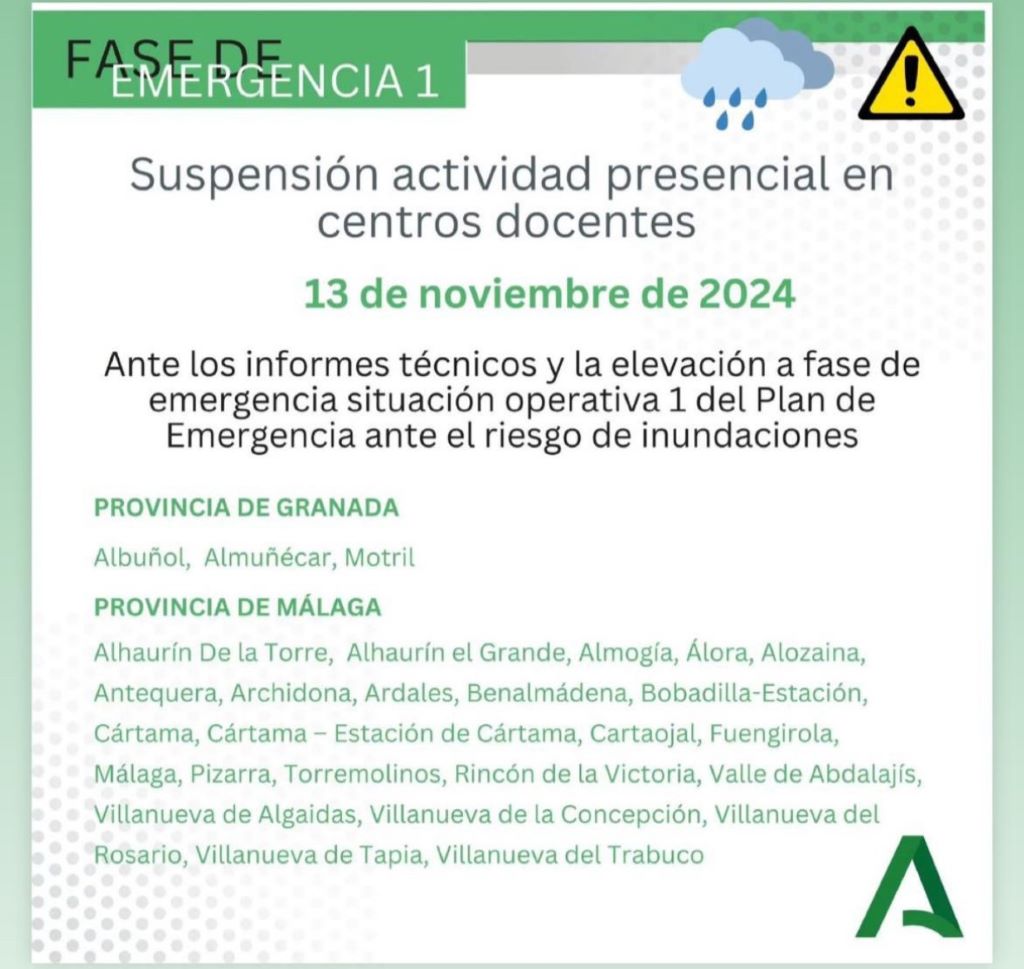

November 14 update: Floods in Malaga

This time we were warned. On the night of November 12, people were resharing AEMET’s red alert warning, schools were informing they would be closed on November 13 and we got the phone alert – with what sounded like a strident, very hard to ignore and loud, continuous sound on our phones, lasting for a few seconds. Different towns had the phone alert at different times, minutes apart – I know that because I was talking to friends in Alhaurín de la Torre after they got their alarm and before we got ours in Benalmadena. We knew it was coming.

Above: the main alerts being shared on the day before the DANA hit Malaga.

We also knew what to do – stay home if you live in an area far from rivers; leave as soon as possible, before the rain comes, if you live in a risk zone. The emergency services were hard at work taking families from risky areas to safer grounds – there were more than 4000 people moved to safer areas in Malaga province, 25 of which in Benalmadena, and public schools were preventively closed in most of the province on both Wednesday and Thursday (November 13 and 14, 2024), which lowered traffic and improved safety considerably.

On November 13, as expected, the DANA came. The most affected areas were the towns of the Guadalhorce Valley – again – and Malaga capital, as well as parts of the Axarquia, on the northeast of the province. The good news is that, at least so far, there were no flood-related deaths in Malaga. I guess alert and prevention really work!

Parts of the capital are inaccessible, though. Public transportation is limited, and health centers are operating at limited capacity. Many streets are covered in water and mud; it is still a bit too early to really see the full consequences of the floods in Malaga. The Costa del Sol had heavy rain and some incidences, but so far relatively small when compared to the capital of the province.

Good news: no floods in Benalmadena (Nov 14)

On November 14, after the red alert had been lifted, I went for a walk around Arroyo de la Miel, in Benalmadena, to see how the area was after the DANA. I’m very glad to add something positive to this post and let you know that our Benalmadena is great. Below, a few images that you may not believe, but I swear were all taken on November 14, after the DANA:

Blue skies, did you see?!? The town looks like it had a good wash, and that’s all. If something, I think it is looking prettier. There aren’t many people out or cars driving on the streets, and some of the shops are closed – perhaps because some of the workers could not get to their workplaces because of the lack of trains; or maybe because the owners decided to close their shops preventively.

Some people were disappointed that the Cercanías train is not working today. Given what could have been, I find it a bit laughable, actually; I’m quite relieved that this is the complaint. Some underground stations on the C1 and C2 lines had some flooding, and Renfe informed they will go back in operation after safety is ensured.

Buses are working; I don’t know if they are at normal capacity, but I saw two 103 at the same time, and this was a first! I also went to the garage under the sports complex, and to my surprise, it was open and working normally – just kinda empty.

I also checked two spots on the little creek that runs along Av. Mare Nostrum, and it looked fine. Ducks were happy, and so was I! And to close on a positive note:

In a series of bad news about the floods in Spain, it is logical that the news focus on the worst consequences of the floods. It is easy to forget that much of the places we love are still there, even in places heavily hit. I’m quite relieved and glad to share that (at least the part I saw of) Benalmadena has resisted so well.

Conclusion

It’s super weird to spend years under a drought and then have floods in 3 different parts of the country almost simultaneously, and I guess the authorities were also caught by surprise by this rather unbelievable sequence of events. Climate change comes to (everybody’s) mind. But there’s more that comes to mind, too.

First and foremost, the lack of preparation. Floods and heavy rain are not 100% predictable up to the last day; you can see how AEMET’s twitter 12 hours before the floods in Valencia forecasted 90 mm of rain (90l/m2), when in reality, it was more like 500 mm. These are very different numbers. If we really can’t foresee rainfall amounts, all the more important it is to be prepared at all times. Prevention, in this case, is done by maintaining the riverbeds.

There are dry riverbeds all over Spain – these are the paths the temporary rivers made by strong rainfalls are supposed to take, and too be contained there. Climate change is intensifying both droughts and rainfalls, which, unfortunately, makes the preservation of riverbeds both harder and more important.

During the dry times, dust, sediments and vegetal parts accumulate on these riverbeds, making it shallower; the sun also contributes by ‘baking’ the soil to some extent, which makes it less permeable. Then, after years of this process, when the rain comes, in bigger than expected amounts, the only possible path is beyond the limited riverbeds – flooding the nearby areas.

Second, sending the alerts to phone on time would indeed have likely spared many lives. I hope the administration can make the alert process a bit more straightforward – which I’m not seeing today, yet. That is, nevertheless, a very last resource, as devastation and material losses would not be prevented by that; saving lives, though, is more than enough reason to alert the population.

Third and finally, there should be some limitation on permits to build near riverbeds. This may be in place, but something didn’t work properly on that side as well, right? Maybe a review of this legislation could spare a lot of damage in the future.

When a tragedy of this proportion happens, it’s important to learn from the mistakes and avoid repeating them. More and/or larger, well-maintained riverbeds, coupled with a review and relocation of people in danger zones and improving the alert protocol seems to be the ways to go. Climate change is not going to stop, so it is foreseeable that floods will not only happen again, but even intensify. It all certainly has a cost, but I believe it’s likely to be less expensive than dealing with the aftermath of a flooding in the proportions of the one in Valencia; not to mention the losses of life, which are irreparable.

Very informative! Gracias